Shana tova!

Traditionally, this Rosh Hashanah drasha is an opportunity to reflect on the lessons of the past year and to offer wishes for the upcoming one. Let me start with an understatement: it’s been a really difficult year. It started with the massacre of soldiers and civilians, teenagers dancing and grandmothers in their kitchens and children playing in their garden. It continued with a war that has cost the lives of thousands more, and put Israel in a situation that would have been hard to imagine a year ago, battling on seven fronts. It’s been a difficult year as the effects of that war rippled out across the world and reached here, prompting increased acceptance of antisemitic acts and speech, increased isolation. Jewish children changed schools, people who hadn’t come to synagogue for twenty years started attending again, seeking a safe space. Friendships and alliances have been tested or torn, either because of arguments or because of silence. It’s been a difficult year — on a smaller scale, since October I’ve been reacting mostly on the short term, finding it difficult to plan anything in the far future. Like many people, I’ve had increased trouble concentrating, sometimes checking the news 150 times a day. With all this in the background, what can I wish us for the upcoming year, which doesn’t promise to be any easier? I want to wish us freedom.

There’s a famous Talmudic debate about the order of certain biblical events. I want to quote it in its entirety, because it’s more complex than the way it’s sometimes presented.

תַּנְיָא, רַבִּי אֱלִיעֶזֶר אוֹמֵר: בְּתִשְׁרִי נִבְרָא הָעוֹלָם, בְּתִשְׁרִי נוֹלְדוּ אָבוֹת, בְּתִשְׁרִי מֵתוּ אָבוֹת, בַּפֶּסַח נוֹלַד יִצְחָק, בְּרֹאשׁ הַשָּׁנָה נִפְקְדָה שָׂרָה רָחֵל וְחַנָּה, בְּרֹאשׁ הַשָּׁנָה יָצָא יוֹסֵף מִבֵּית הָאֲסוּרִין. בְּרֹאשׁ הַשָּׁנָה בָּטְלָה עֲבוֹדָה מֵאֲבוֹתֵינוּ בְּמִצְרַיִם, בְּנִיסָן נִגְאֲלוּ, בְּתִשְׁרִי עֲתִידִין לִיגָּאֵל. רַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ אוֹמֵר: בְּנִיסָן נִבְרָא הָעוֹלָם, בְּנִיסָן נוֹלְדוּ אָבוֹת, בְּנִיסָן מֵתוּ אָבוֹת, בְּפֶסַח נוֹלַד יִצְחָק, בְּרֹאשׁ הַשָּׁנָה נִפְקְדָה שָׂרָה רָחֵל וְחַנָּה, בְּרֹאשׁ הַשָּׁנָה יָצָא יוֹסֵף מִבֵּית הָאֲסוּרִין, בְּרֹאשׁ הַשָּׁנָה בָּטְלָה עֲבוֹדָה מֵאֲבוֹתֵינוּ בְּמִצְרַיִם, בְּנִיסָן נִגְאֲלוּ בְּנִיסָן עֲתִידִין לִיגָּאֵל

Rabbi Eliezer says: In Tishrei the world was created; in Tishrei the Patriarchs were born; in Tishrei the Patriarchs died; on Passover Isaac was born; on Rosh HaShana Sarah, Rachel, and Hannah were remembered by God and conceived; on Rosh HaShana Joseph came out from prison; on Rosh HaShana our forefathers’ slavery in Egypt ceased; in Nisan the Jewish people were redeemed from Egypt; and in Tishrei in the future the Jewish people will be redeemed.

Rabbi Yehoshua disagrees and says: In Nisan the world was created; in Nisan the Patriarchs were born; in Nisan the Patriarchs died; on Passover Isaac was born; on Rosh HaShana Sarah, Rachel, and Hannah were remembered by God and conceived; on Rosh HaShana Joseph came out from prison; on Rosh HaShana our forefathers’ slavery in Egypt ceased; in Nisan the Jewish people were redeemed from Egypt; and in Nisan in the future the Jewish people will be redeemed.

Very often, this text is used in order to say something about the nature of Rosh Hashana as the anniversary of the creation of the world. (Already we see that we’re not meant to take this statement literally, else there would be no debate.) One opinion is that the creation is more like Nissan, the springtime. The trees start to blossom, the flowers open, we feel a sense of beginning. The other opinion, and the one that was accepted, is that the kind of creation that we’re talking about is that of the autumn, where the fruit on the trees and the crops in the fields represent the completion of creation. Just as the creation story presents Adam as fully-formed, and ready to fulfill his potential to develop (or to destroy) the world, the time of fully-formed fruit in the autumn is an appropriate season to locate this story in.

It’s an interesting debate, but for me there’s another important detail in the text, which is what the two rabbis surprisingly agree on: on Rosh Hashana, Joseph was released from prison, and on Rosh Hashana, the slavery in Egypt ceased. This is unanimously accepted, but not so well known. We usually associate the liberation from Egypt with the festival of Pesach, but we see here that freedom and liberation are not identical. For six months before they left Egypt, they were no longer slaves. What did they do for those six months? I don’t know of any traditional sources that describe their experience during this turbulent time, but following in the tradition of the hasidic masters, such as Rebbe Kalonymous Kalman Shapiro, who emphasised imagination and visualisation of biblical scenes, I imagine the people moving between fear and excitement, not yet able to celebrate, and unsure what the future would bring.

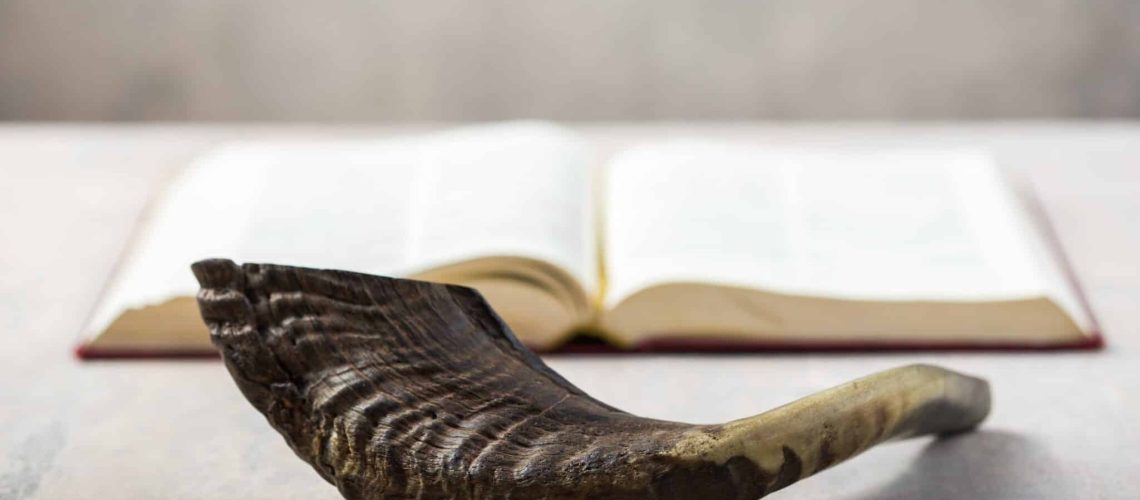

When I imagine Joseph released from his prison, I don’t see a day of celebration, but also terror as he’s brought before a psychopath dictator, not knowing if he’ll finish the day dead or alive. Liberation is worth celebrating, but freedom is more complex. Liberation is an action, and freedom is potential. If you want a visual metaphor for this, let’s remember that most of the festivals, including Pesach, are in the middle of the month when the moon is full. Rosh Hashana is the only festival when the moon is covered up, bekeseh leyom chageinu [Psalms 81:4], and its presence is only a promise, not yet visible. Freedom can be born in the darkness. Or if I think of liberation in terms of music, I think maybe of jazz, or the messy singing around the Seder table, a mish-mash of melodies and stories. Compare that with the music of Rosh Hashana, the shofar, an instrument capable of producing one single note of pure potential. That is the difference between liberation and freedom.

The key idea of Rosh Hashanah is that of teshuva, usually translated as repentance, but it’s much more than asking for forgiveness. At its core, it’s an acceptance of the possibility that I can change, that the person that I am today is not imprisoned by the person I was yesterday. Perhaps the idea of a divine tribunal that decides who will live and who will die, who by war and who by fire — this confrontation with our mortality, without our regular comfortable illusions — all this is to reinforce the uncomfortable truth that we don’t know what’s going to happen with our lives. We don’t know that tomorrow will be like yesterday. There’s something wonderful about this truth, the potential to change, and it’s true that we approach this day of judgement with confidence, celebrating it with good meals and shofar blasts. But there’s also something terrifying, if we take the words that we read seriously. We don’t know how this story is going to turn out. Anything can happen, in teshuva. Rebbe Nachman says [Likutei Moharan 6] that the process of teshuva is linked to the highest name of God, Ehyeh asher Ehyeh, I-shall-be-who-I-shall-be. He says that during this time of year we are all reflections of that divine name that indicates freedom and change, and quotes the enigmatic words of the Zohar – Ana Zamin Lemahevei – “I am prepared to become”. Become what? We don’t know.

When I came to Adath Shalom, just over three years ago, just before Rosh Hashana, I was excited and scared, and prepared to ‘become’, without knowing exactly what to expect. It was towards the end of the difficult Covid period, and the question was whether and how to continue to bring people back to the synagogue. On the whole, that’s no longer our question. The community survived, recovered and has gotten stronger, although we bear certain scars from that period. It’s only three years, but a lot has happened. There are people who are no longer with us. My daughter was born, Elkana’s daughter was born, there are non-stop activities in the synagogue and non-stop emails being sent to you to remind you of special events. And at the same time, a protracted feeling of crisis. War on the eastern borders of Europe, war in the Middle East, difficult election choices in France, and every summer is the hottest summer on record — we try to find ways to react to all of these, and it’s hard to know what tomorrow will look like, let alone imagine with any clarity our lives in five or ten years.

My dream is to be a rabbi of a boring community in boring times, but the world is not letting that happen. Rivon is retiring this year, and I’m not Rivon, nor will I ever be. And yet, with all this, I’m very confident. Confident in the people around me, the people here today, confident in the the future, confident in our potential. I don’t know what this coming year will look like, but Ana Zamin Lemahevei, I’m ready to become.

This is the freedom we are celebrating on Rosh Hashanah.